Television this week sees the return of Professor Bernard Quatermass in a near dramatic serial in six parts. Scriptwriter NIGEL KNEALE recalls here the first ‘Experiment’ and introduces the sequel, ‘Quatermass II,’ which begins on Saturday

A man-carrying rocket is fired into space, as a limited experiment, to reach a height of 15,000 miles. Something goes wrong. When the rocket is eventually brought back to earth by remote control, only one of the crew is found alive. Unable to give any account of his experience, he starts to undergo a rapid and terrible transformation. It becomes apparent that he is now the helpless carrier of an unknown life-form. As it encounters other earthly orders – vegetable, fungoid, animal – a monstrous amalgam is formed, with the faculty of infinite reproduction. It is destroyed just in time to prevent catastrophe to the world.

This was the theme of The Quatermass Experiment, the television serial which I wrote and Rudolph Cartier produced just over two years ago. Part of the impression it made was perhaps due simply to being the first of its kind – in this country at least. But when reviewers used phrases like horrific fantasy one was tempted to wonder: gust how fantastic.

Since the date of that production, and particularly during the past few months, exploration beyond the earth’s atmosphere has become an imminent fact. Artificial satellites are in prev partition at this very moment. America, Britain and Russia have announced plans – the latter even of employing a man-carrying rocket. A dividing line has gone: stories of the future have become stories of the present.

Too horrific? The very nature of the official researches now begun – speculative, cautious – emphasises our ignorance of what may be encountered beyond the air. Fifty years ago scientific materialism was ready to declare: ‘There is nothing! A dead void.’ Could life exist elsewhere in the solar system? ‘Impossible!’ These confident answers have lost their validity, along with the theories on which they were based. Something more is known of the nature of life and energy. Today’s scientist, asked the same questions, limits himself to a careful: ‘We do not know.’

Man is on the edge of a new wilderness, darker than any unknown continent -in an old-time traveller’s tale. His kind has conquered desert and tundra, but here he is unfitted by nature to penetrate. He may face subtle destruction by the very emptiness – or encounter energies and forces beyond his power to calculate, and ills that no flesh is heir to.

One thing is certain. Even the preparations for such exploration will be infinitely long and arduous. There will be a record of disappointments, failures, at times the same loss of faith in a particular enterprise that Columbus met. It is such a spell as this – of technical doldrums – that forms the background to Quatermass II.

The time is some years after the first disaster. Professor Bernard Quatermass has continued his work. Prototypes of a second, more powerful nuclear-powered rocket have been built (the Mark II of the title), to form the basis of an ambitious long-term ‘Moon Project.’ Then, in the early stages of testing, comes a crushing setback. His research is at a standstill, perhaps at an end. As he tries to come to terms with the situation, there is a curious interruption.

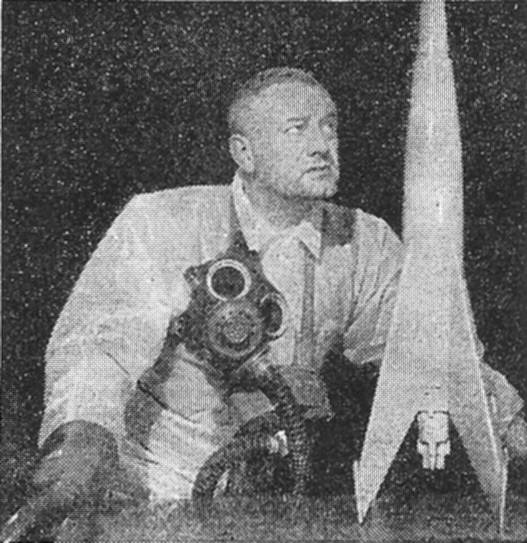

The new serial, then, has no direct connection with its predecessor. (In fact I have been at some pains to make the distinction clear, as a film version of the ‘Experiment’ is to be generally released almost simultaneously with this production, and confusion could arise.) None of the earlier characters has been held over, apart from Quatermass himself. This part is being played by John Robinson, following the tragic death of Reginald Tate, its originator, a few weeks ago. With new production facilities and effects, Rudolph Cartier and I are trying for something different in atmosphere and story. We hope it works.

John Robinson as Professor Quatermass

References

Kneale, Nigel. “To A New Wilderness.” Radio Times, no. 1666 (October 14, 1955): 7.