All photos by Alex Briggs

Collecting the work of Nigel Kneale is to some extent a frustrating task, as there is always the feeling that in an ideal world there should be so much more of it. A large percentage of his work for television doesn’t exist in a collectable form, either because it was broadcast live and not recorded or, even worse, it was recorded and the tapes were destroyed. Even some of his work which does survive in the archives remains locked away and inaccessible to the general public, unless they can make it to an all-too-rare screening. But I shouldn’t complain too much, because in the 25 years or so that I’ve been collecting Kneale’s work there has been an increased interest in the type of drama in which he specialised, meaning that classic plays and serials which were formally only available on the collector’s circuit via low quality VHS copies can now be purchased as lovingly remastered DVDs with detailed viewing notes. And very early on I struck lucky with some of his rarer items, purely by making my enquiries at just the right time.

My earliest association with Kneale’s work came with the TV Times and Starburst magazine’s coverage of the 1979 Quatermass serial. I wasn’t invited to stay up and watch it with my parents, but the combined images of an ancient stone circle and a future Britain in disarray were enough to make me feel I had shared in the collective experience. By the following summer I was considered old enough to watch BBC2’s late-night horror double bills, as well as the TV series Hammer House of Horror, and my immediate interest was rewarded with a book on Hammer Films, packed full of age-inappropriate photographs. But the photos from the first two Quatermass films seemed to belong to a different genre altogether, with a bleakness that struck deeper than the nudity and gore of the later Hammer classics. In 1981 I watched and enjoyed the sitcom Kinvig, unaware that it had anything to do with Quatermass. Then in the late 80s I finally caught a late night screening of Quatermass & The Pit and was immediately hooked. Packed full of fascinating ideas and allusions, and with that terrifying climactic image of the devil rearing over London which left me reluctant to to go straight to bed, I knew that Kneale was a writer whose work was worthy of thorough investigation. A trip to the local video rental shop turned up the BBC’s 3-hour VHS edit of the original 1958 serial, and it turned out to be even better than the Hammer film.

In those pre-internet days information was hard to come by, but somehow I found the address of a tape-trading circle, and was astonished to find that reasonably watchable tapes of the other surviving Quatermass episodes, along with Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Stone Tape and The Year of the Sex Olympics were actually in circulation and could be obtained in exchange for something similarly desirable or (if the owner was feeling generous) a blank tape and return postage. Around this time a VHS release of Kneale’s celebrated TV adaptation of The Woman in Black and the televising of his 4-part version of Kingsley Amis’s Stanley and the Women provided welcome additions to the collection, and I even found collectors who had off-air recordings of lesser-known one-off plays Ladies’ Night and Gentry. But there had to be more if you looked hard enough.

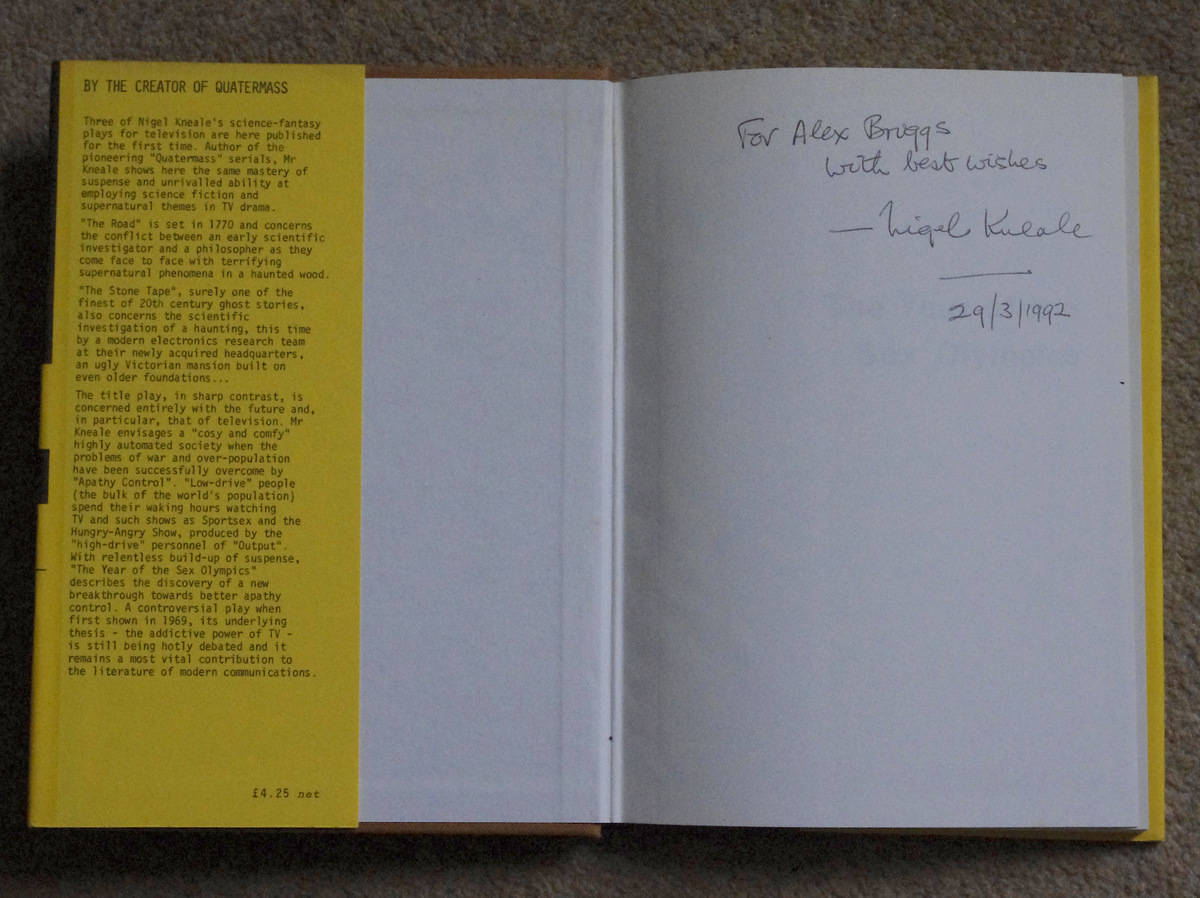

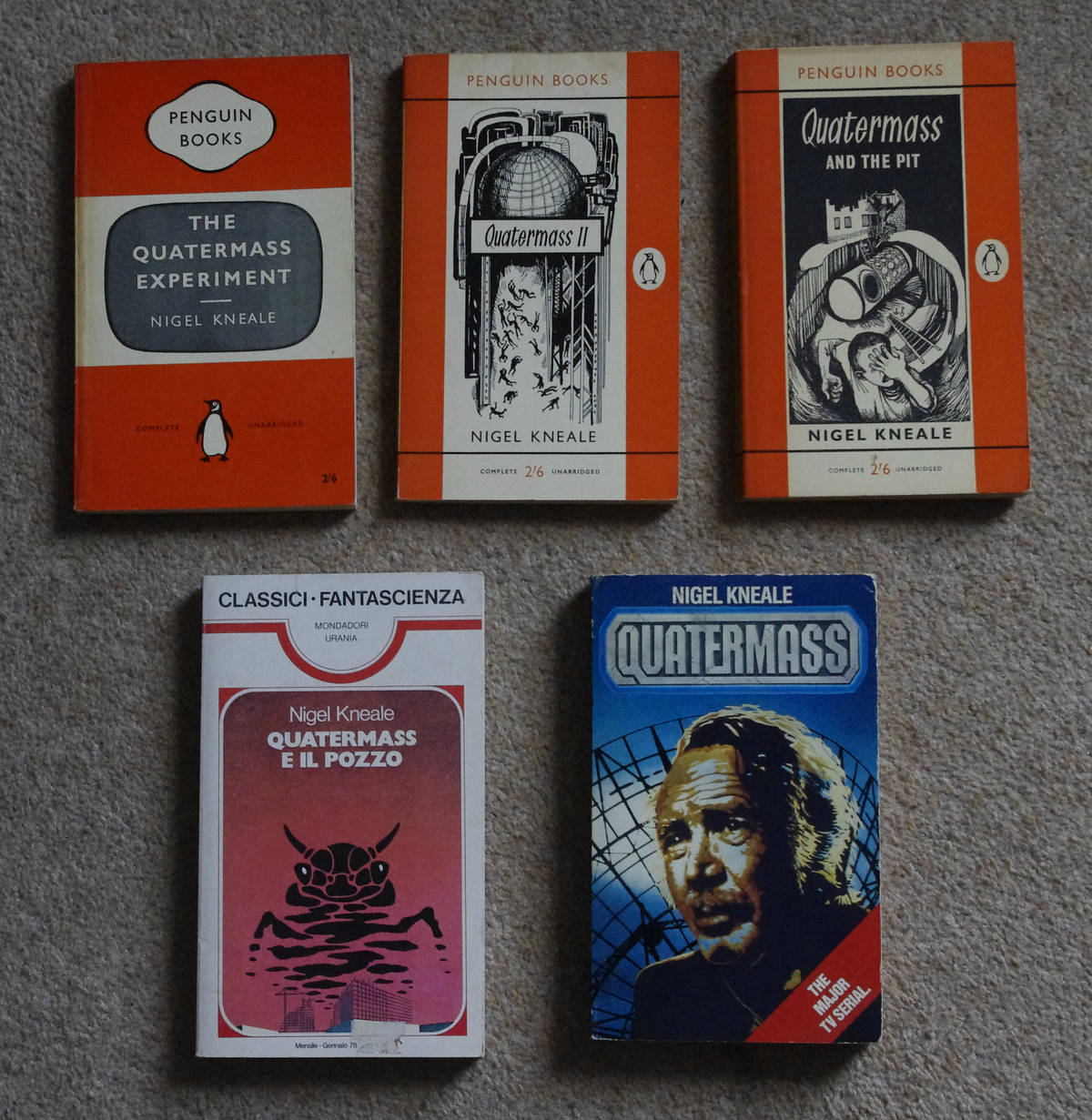

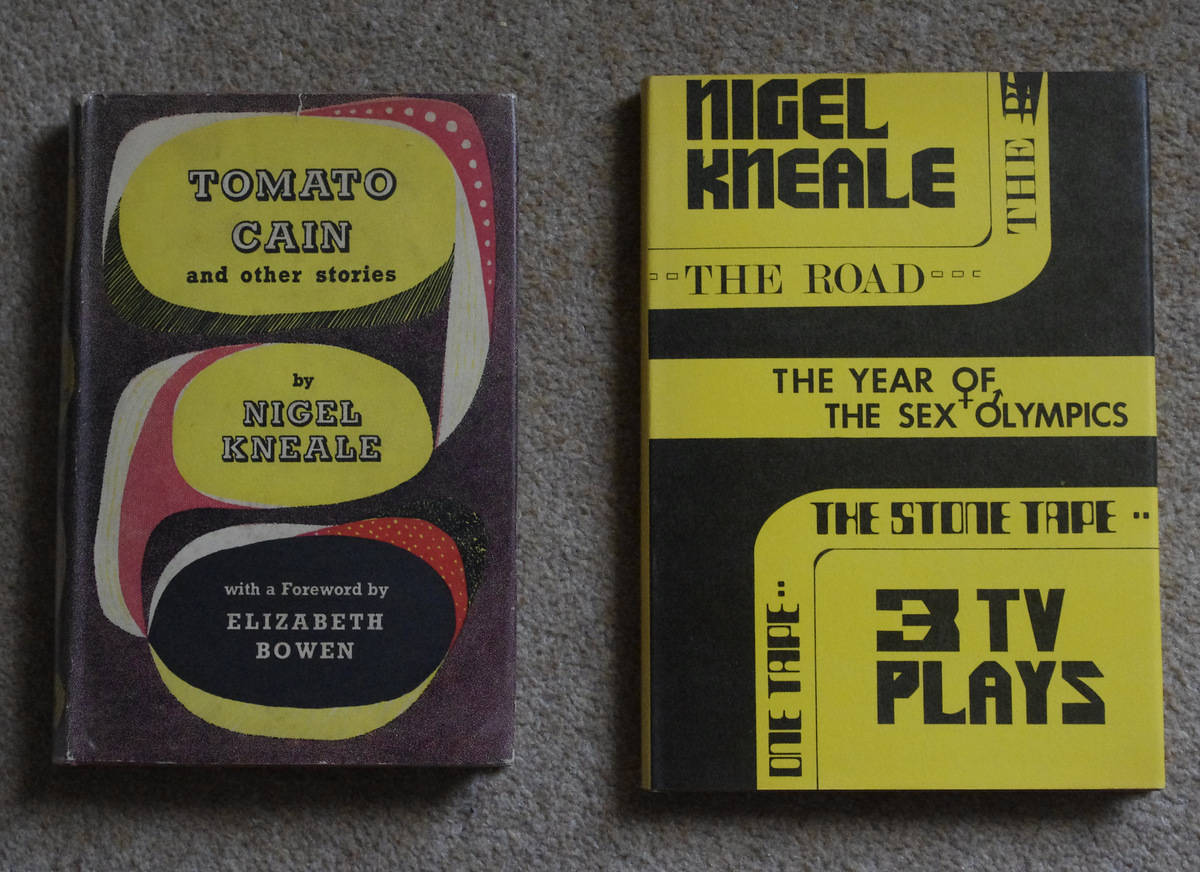

Potted biographies in reference books always started off by mentioning that Kneale’s first success was with a book of short stories entitled Tomato Cain, for which he won the Somerset Maugham Award in 1950. In an attempt to track down a copy I placed a “Wants” ad in Book & Magazine Collector to which I got just one response, from a dealer who had an original hardback edition, complete with dustjacket. Seemingly unaware of its rarity, he was offering it for a meagre sum, probably no more than £5. Also around this time I started picking up the original Penguin script books of the first 3 Quatermass serials, as well as Kneale’s own novelisation of the fourth. Browsing in a second-hand bookshop in Richmond I came across The Television Playwright, a 1960 collection of BBC scripts including Kneale’s Mrs Wickens in the Fall. However there was one book shown in publishers’ lists as being in print, but which no bookseller seemed able to order in for me. This was The Year of the Sex Olympics: 3 TV Plays, a book made particularly desirable by its inclusion of the script for 1963’s The Road, which even then had quite a reputation as one of the great lost television plays; a chillingly well-realised clash between science fiction, the supernatural and period drama with a devastating denouement. Of course the BBC had seen fit to wipe their recording of it, and so reading the script was the only way of experiencing its greatness. The crucial moment came when I enquired in a now long-gone science fiction book shop in East Sheen. The shopkeeper knew of the book; it was a privately printed volume produced by a mail order publisher and he’d never actually seen a copy. But he did helpfully suggest “Why don’t you write to the author?” This might have seemed like a ridiculous suggestion were it not for the fact that on the August bank holiday the previous year the BBC had screened an episode of Quatermass II as part of a day of programmes commemorating the closure of their former studios at Lime Grove, and my mother had casually mentioned that Nigel Kneale lived locally. Not ony that, she knew his address, having been good friends with his former next door neighbours. So I wrote a letter, not sure whether to expect a reply, as I’d been led to believe he was something of a recluse. But the following Sunday morning the telephone rang and it was Kneale himself. I hadn’t had the temerity to include my phone number in the letter so he must have gone to the trouble of looking it up in the directory. He told me his agent had just sent him a box of unsold copies of the book in question and I was welcome to pop round and collect one. Five minutes later I was standing in Nigel Kneale’s front room, with that familiar painting on the wall depicting the author himself stood next to the alien spacecraft from Quatermass & The Pit. We had a bit of a chat about the availability of his work on VHS, and his attempts to get more of it released. I decided not to mention having bootleg tapes of some of the shows, just in case he disapproved. He gave me the promised book, already signed and dedicated, and then I was on my way back home, not quite believing my luck.

In the intervening years, Kneale’s desire to make more of his work widely available has been fulfilled thanks to the arrival of the DVD format, allowing the BBC, the BFI and specialist labels such as Network to cater more easily to the demands of fans of vintage television. Therefore somebody starting out nowadays is able to instantly add a programme to their collection in optimum quality rather than begin with a “make do” version followed by a gradual series of “upgrades.” An example from my own experience would be Late Night Story, a series of horror stories on the theme of childhood read by Tom Baker and broadcast by the BBC during Christmas week 1978. I’d never seen this in any lists of Kneale’s TV work, only learning of its existence by chance when perusing old copies of the Radio Times, and being very excited to see it included a reading of The Photograph, one of my favourite stories in Tomato Cain. Through my contacts with fellow collectors I soon managed to obtain an audio cassette recording, created by the collector himself via the time-honoured process of pointing a microphone at the TV speaker during the programme’s one and only transmission. This worked perfectly well for the collection, and there seemed to be little chance of ever viewing or even owning a video recording of this obscure entry in the Kneale catalogue. But then about a decade later I got a chance to watch the original programme courtesy of the BFI, who dusted it off for an already unmissable event at the National Film Theatre, a screening of The Stone Tape followed by an interview with Kneale himself. Understandably this sold out pretty quickly and I had to queue up on the day for last minute reserve tickets, but I made it in and got to enjoy the added dimension of seeing as well as hearing Tom Baker’s unique story-telling skills. A few more years passed and then eBay appeared, and for a while (until the rules on selling copyrighted material got tightened) a wealth of rare and obscure TV programmes began turning up for sale, usually time-coded copies taken from BBC Worldwide’s library. Amazingly, the complete series of Late Night Story was one such programme, and I was able to add it to my DVD collection in very acceptable quality. Little did I know that shortly after this I’d be able to upgrade to a perfect copy of the series; in fact it took me quite a while to discover that the BBC had even given it an offical DVD release, hidden away unheralded among the typically generous bonus features on the Doctor Who – Key To Time box set. Ironically, Kneale had finally got his name on the credits of a Doctor Who release after years of watching in dismay as the programme shamelessly plundered his own work for ideas.

For some items in the catalogue, this cycle of wider availablility is awaiting completion. I remember in the early 90s booking a viewing of the 1962 Kneale/Cartier adaptation of Wuthering Heights at the BFI’s viewing room in Stephen Steet and being handed a pile of canisters containing separate reels of film for me to load onto a tabletop viewer by myself. I believe it is now available for viewing on demand in a more user-friendly digital format at the BFI Southbank library, but it is still awaiting a TV repeat or DVD release. And then, of course, there is the legendary 1954 adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four, which has been in circulation among collectors for decades, was given a BBC4 repeat to mark the passing of producer/director Rudolph Cartier, and even seemingly made it into the Public Domain in the USA where it received a low budget DVD release. But the by all-accounts magnificent restoration job carried out at great expense by DD Entertainment still remains unseen, thanks to the mysterious movements of the Orwell Estate who have twice granted permission for its release on home entertainment and then changed their minds at the eleventh hour. One hopes that within the next few years, when the copyright expires, the BFI will be able to release their planned DVD and include the recently recovered 1965 remake as an extra.

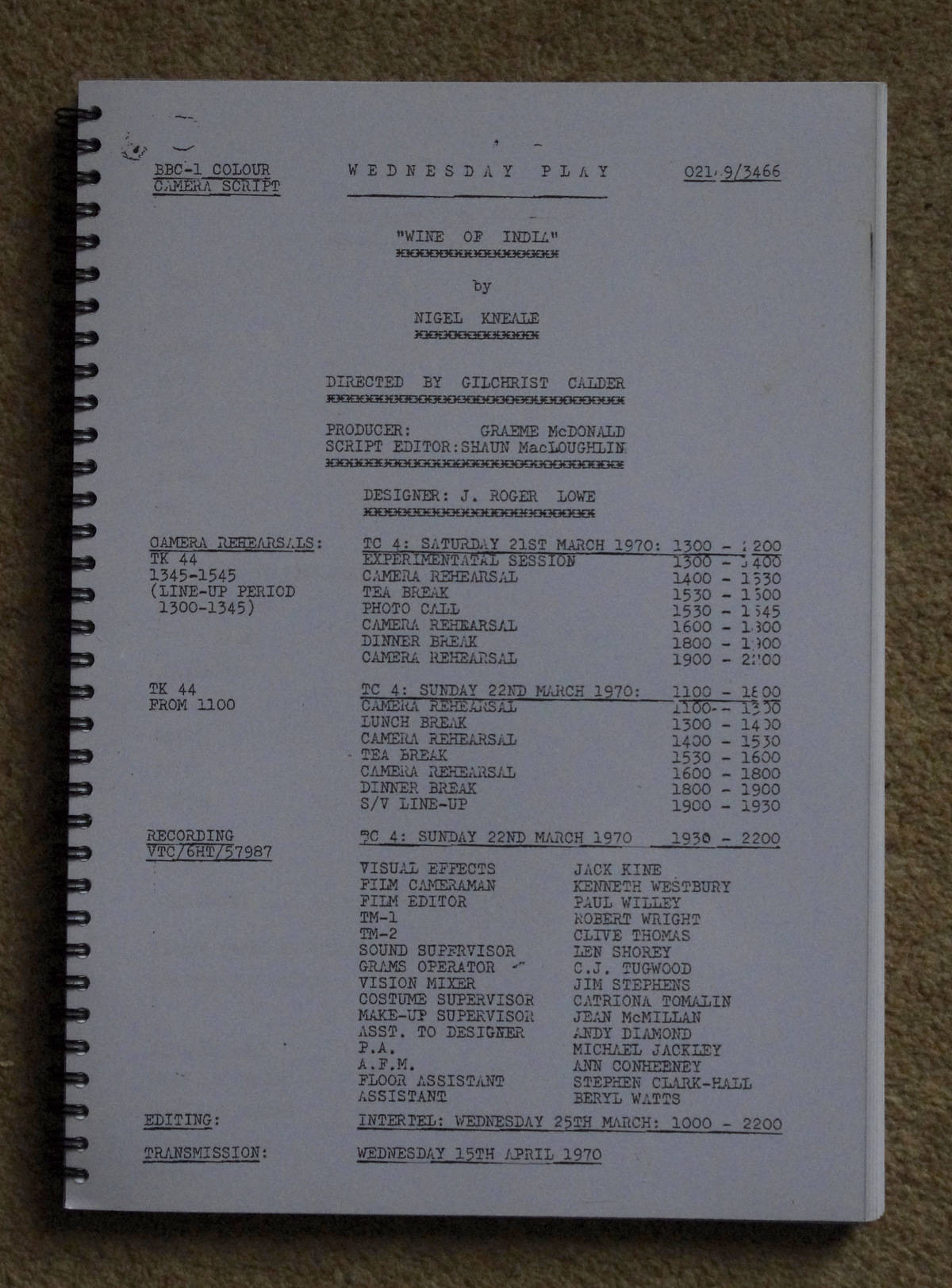

So the frustration of being a Kneale collector continues, as these and other gems (including 1964’s nuclear drama The Crunch) remain locked away in the archives. And then, as previously mentioned, there are the classic works which should be in the archives, but have long been lost or destroyed, with the BBC being particularly culpable due to their wiping of such classic plays as The Road, Bam Pow Zapp! and Wine Of India. Amateur re-stagings of some of these have appeared on YouTube, and are very welcome in lieu of the originals, but it is sad to think that Kneale fan Mark Gatiss tried and failed to get the BBC to produce an official remake of The Road, its continuing power confirmed by a superb read-through at London’s Horse Hospital in December 2015 which included Gatiss himself among the cast.

A further big hole in Kneale’s filmography is the large number of treatments and finished screenplays which never made it into production. Adaptations of Brave New World and Lord of the Flies, a poltergeist film for Ealing Studios, the ambitious and highly controversial 6-part serial The Big Big Giggle - these and many others would have added substantially to an already impressive CV. Occasionally “new” titles do get added to the Internet Movie Database, for example long-forgotten re-makes of Wuthering Heights and The Road produced for Australian television in 1959 and 1964 respectively, raising hopes that telerecordings may still exist somewhere. And then there is a rogue title that appeared on Wikipedia and IMDb for a few years, which turned out to be a work of fiction in more ways than one. The October Wedding was supposed to be a British film from 1959 starring Ian Hendry and directed by an enigmatic Russian director named Yuri Gadyukin, who was also credited as having co-written the screenplay with Nigel Kneale. A Google search even brought up a convincing French poster design and memories of a late-night screening by Channel 4 during the early 1990s. Eventually the whole thing was revealed to be a hoax, staged by a couple of would-be film-makers who wanted to set up a convincing internet presence ahead of a “documentary” feature about a cult film director who died in mysterious circumstances.

Poster design represents a whole different area of interest for the Kneale collector, since his work with Hammer Films means there is plenty of publicity material to seek out from the worldwide territories where the movies were released. This is an unavoidably pricey corner of the market, but the occasional bargain can be picked up when you’re least expecting it. For example, I found the original US poster for Quatermass & The Pit (superior in design if not title to the UK version) for 30 Australian dollars in a Melbourne junk shop. Perhaps the most desirable poster is the Polish design for Zemsta Kosmosu (Revenge of the Cosmos aka The Quatermass Xperiment) with artwork as unique as its title. The Italian editions of the Quatermass script books are also worth seeking out for their excellent cover designs. Further collectable printed material would include copies of the original scripts, which turn up on eBay now and again. Several years ago I got outbid on a copy of the script for the lost Out of the Unknown episode The Chopper, and have never seen it turn up since. But some consolation was had later on in the form of the script for Wine of India, which cost me little more than the seller would have spent on photocopying it.

Considering the enormous impact Kneale’s classic work had on developments in British television and cinema, it is a shame that nowadays he is not as well known as many of his contemporaries in the field. A planned 90s anthology series entitled Push The Dark Door might have re-established Kneale as a familiar name to mainstream audiences, not that this was something he seemed particularly bothered about. After all, in the early 1960s he’d turned down opportunities to help kickstart two long-running franchises, his track record with original drama as well as adaptations making him a first choice writer for both Doctor Who and the big screen version of Ian Fleming’s Dr. No. It is perhaps partly because of this refusal to work on potentially lucrative projects if they didn’t suit his tastes that his enormous legacy is still something of a well-kept secret. But thanks to the growth of such internet-born movements as the Folk Horror Revival, which cites Kneale among its key reference points, more and more people are discovering and seeking out his work. Hopefully this renewed interest and recognition will result in more of Nigel Kneale’s innovative and stimulating work becoming available to the collector.